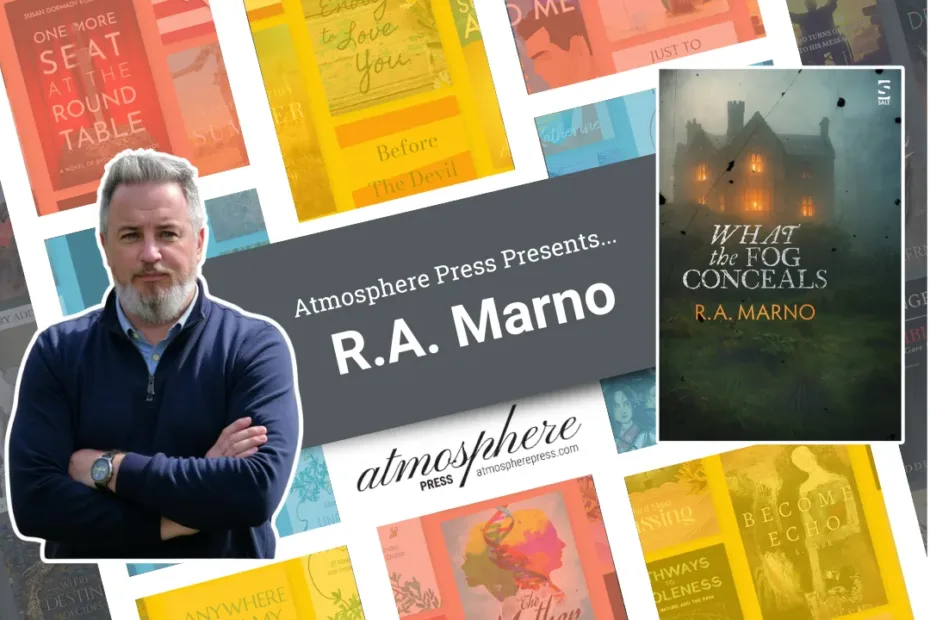

An Interview with R.A. Marno

R.A. Marno is an award-winning film director and writer based in Belfast. His fiction combines literary precision with a dark psychological undercurrent, exploring themes of memory, loss, and the quiet ruptures of ordinary life. What the Fog Conceals is his debut novel. In addition to his work in fiction and film, Marno has contributed to a range of creative and cultural projects across the UK and Ireland.

Marno writes literary gothic fiction that reimagines the haunted past – stories where belief, guilt, and memory twist through human lives across centuries. His prose is precise, restrained, and atmospheric, drawing on his background in film and his fascination with silence, architecture, and the psychology of space.

Inspired by authors such as Sarah Waters, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Shirley Jackson, Marno’s work balances restraint, ambiguity, and atmosphere. His fiction often returns to themes of silence, complicity, and the ghosts of memory. A lifelong diver, he’s deeply connected to the sea and concerned about oceanic conservation – linking environmental loss to the emotional erasures explored in his stories.

What inspired you to start writing this book?

It began with a half-remembered story – Audley’s Town, a vanished village in County Down. Mid-nineteenth century, roughly 250 people; a few years later, gone. Locals say the tenants were put on a ship called The Rose bound for America, yet no record of the vessel exists. What hooked me wasn’t the mystery but the silence around it: how an erasure that complete can sit in plain sight and be politely ignored.

I didn’t want to retell the history; I wanted to test the psychology of omission. What does it cost a community to agree not to name what’s missing? The book follows that thread – not ghosts, but the damage done by what’s left unsaid. That’s always been my territory: places where truth blurs and people carry on regardless.

Tell us the story of your book’s current title. Was it easy to find, or did it take forever?

Forever. I cycled through a stack of near-misses that sounded right and meant nothing. What the Fog Conceals arrived late and immediately reframed the book. Fog both hides and reveals; it lets you see the outline while denying the detail. That’s the reading experience I’m after – partial knowledge. The feeling that you’re close enough to sense the shape, never close enough to be sure. Once that title landed, the drafts tightened. It gave me a governing metaphor without boxing the story in.

Describe your dream book cover.

Something pared back – muted tones, a house half-swallowed by fog, light at the windows. I like covers that feel like weather, where mood carries meaning before a word is read. The final design does exactly that: quiet menace, distance, a suggestion rather than a statement. No faces, no clues, just the sense that something is present and refusing to declare itself. That restraint matches the prose.

If your book had a soundtrack, what are some songs that would be on it?

I grew up on eighties and nineties rock – Metallica, Nirvana, Guns N’ Roses, AC/DC. It isn’t about volume; it’s control and release. Nothing Else Matters has the ache of restraint. Smells Like Teen Spirit carries restless defiance – pressure looking for a fracture. November Rain is the slow build to collapse. The book runs on that rhythm: tension held to breaking point, emotion delayed until it can’t be delayed any longer. That’s how I write – disciplined on the surface, volatile underneath.

What books are you reading (for research or comfort) as you continue the writing process?

I return to Sarah Waters’ The Little Stranger and Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant – both use restraint as architecture, not ornament. Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House sits on the desk as a reminder that atmosphere is an argument, not a backdrop. When the fiction starts drifting, I read folklore and local history. Real strangeness is steadier than invented strangeness; it keeps me honest and anchors the tone.

What other professions have you worked in? What’s something about you that your readers wouldn’t know?

Finance, film, adventure sports, and mediation. I’ve built companies, made films, and spent years teaching people how not to panic on cliffs. I also represented Northern Ireland in taekwondo and won a Commonwealth Games bronze medal. On paper, that’s a strange mix; in practice, it’s one theme – pressure. Numbers, cameras, heights, conflict: you learn how people behave when something is at stake. That training shows up on the page as discipline and patience. I don’t rush the reveal; I let pressure do the work.

Who/what made you want to write? Was there a particular person, or particular writers/works/art forms that influenced you?

Film taught me first – rhythm, framing, negative space. Directors like Christopher Nolan and Panos Cosmatos showed me how tone can carry meaning. On the page, Ishiguro and Shirley Jackson proved that silence can be more revealing than confession. None of this arrived as a lightning bolt. I realised slowly that I wasn’t writing about events; I was writing about omissions – the emotional archaeology under a place or a family. Once I accepted that, the work found its voice.

Where is your favorite place to write?

Early morning, before the world makes demands. Usually my desk: cold coffee, a mess of notes, quiet. If I’m stuck, I go to the coast. The sea has an indifference that resets me – it doesn’t care if a paragraph lives or dies, which is oddly freeing. I write best where there’s distance – enough space for the sentence to breathe.

What advice would you give your past self at the start of your writing journey?

Stop performing. Write what’s true, even if it makes you look unsure for a while. Style arrives once you stop imitating it. Guard your hours. And don’t wait for permission – no one is coming to tap you on the shoulder. Decide it matters and get on with it. You learn by finishing, not by talking about finishing.

What’s one thing you hope sticks with readers after they finish your book?

That the worst horrors aren’t supernatural; they’re ordinary. They live in the quiet agreements that let things vanish. If a reader closes the book and starts noticing the silences in their own world – the things people choose not to name – then the story has done its job.

Are you a writer, too? Submit your manuscript to Atmosphere Press.

Atmosphere Press is a selective hybrid publisher founded in 2015 on the principles of Honesty, Transparency, Professionalism, Kindness, and Making Your Book Awesome. Our books have won dozens of awards and sold tens of thousands of copies. If you’re interested in learning more, or seeking publication for your own work, please explore the links below.