An Interview with Janet Burroway

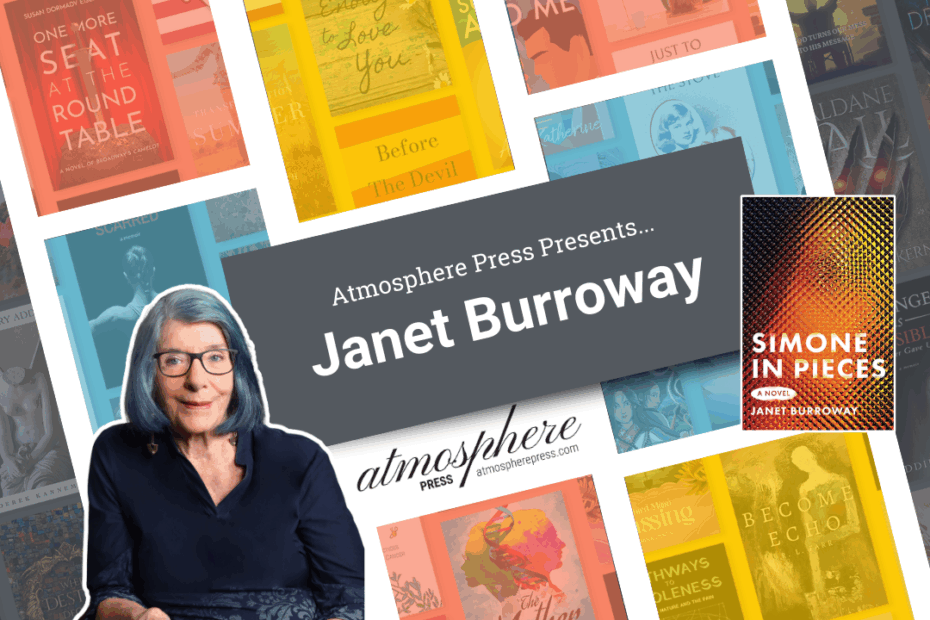

Janet Burroway is the author of poems, plays, essays, children’s books, a memoir, and nine novels, including The Buzzards, Raw Silk, Opening Nights, Cutting Stone (all Notable Books of NYTBR), and Simone in Pieces, due out November 2025. Her Writing Fiction, the most widely used creative writing text in America, is now in a tenth edition, her four-genre text Imaginative Writing in its fifth. Her plays have been produced and read in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and London. Her stories and poems appear in many literary magazines, including Prairie Schooner, New Letters, Narrative Magazine, and Five Points. She is Robert O. Lawton Distinguished Professor Emerita at the Florida State University and winner of the Florida Humanities Lifetime Achievement Award. www.janetburroway.com.

Who/what made you want to write? Was there a particular person, or particular writers/works/art forms that influenced you?

I was always pretty much a doer—or maybe I just mean an imitator. When I saw a play, I immediately wanted to act, and insisted my mom take me to auditions. When she made me a dress, I wanted to make one for my doll, and then to design gowns for my paper dolls out of wallpaper samples. We often went to the library, so of course I wanted to write, composed my first poem at five (it was about Jesus) and supposed I was writing a “novel” in a tiny notebook when I was in grammar school. Those three desires stuck with me into and past my teens, and the one that stuck longest was the writing. Partly this is because my brother was a budding journalist, and I adored my brother. I think ultimately—and I wonder about this, the selfishness of it, and the contemplative aspect of it too—that though I enjoyed company, I liked being alone the best. Solitude drew me. I liked costuming a play better than being in one, and writing a play better still—and yet, when I’ve done so and am in rehearsal, I think I would like nothing better than to be in rehearsal forever..

What inspired you to start writing this book?

Some thirty years ago—which means I was teaching at FSU and had already published Cutting Stone—I had the notion of writing a satirical short story about an English department meeting. I was working at it on weekends, probably through a spring break or part of a summer. It eluded and frustrated me, and then it took a hard turn into grief. I was astonished. I had to work out the entire life of the protagonist to make this ending work. When I told the woman’s multi-decades story to my husband Peter, he said, “That’s your next novel.” But it wasn’t. There was my own grief to deal with when my elder son died, a memoir of him, another novel, a couple of edited anthologies, many poems, the updating of my text books. In between I wrote parts of the woman’s life story, from the many points of view of the people she ran into, or befriended, or became close to, and only gradually from her own point of view, so that the reader comes to know her as I did, only gradually, as one often comes to know someone in life. Some vestiges of the original satire remain—especially some of the made-up names of the multi-generational faculty at her final teaching job. Can you get: Nuke Riddick, Nan Seckwitter, Harriet Glaucia?

Tell us the story of your book’s title. Was it easy to find, or did it take forever?

Oh, the struggle of the title! As my concept of the book evolved, so that I wavered over its parts, wrote and trashed a bunch of them, rewrote others from another viewpoint—and so forth—it was called Montage, and then, after a 1930’s montage that figures in the story, Indian Dancer, and then just Simone, and then because Simone travels from Belgium to England to America and across America in as many kinds of conveyance as there are chapters, Simone in Transit, and then at the suggestion of my good editor Lloyd Dennis, Simone in Pieces, which is both the way Simone must construct her self and the way you construct the story as you read it.

If your book had a soundtrack, what are some songs that would be on it?

What fun it would be to figure it out. From the forties, “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” and “This Is the Army, Mister Jones” to “La Boheme” and cool jazz as Simone comes of age, to “The Times They Are A-changin’” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” in the seventies, to “Dock of the Bay” (wastin’ time) to any Leonard Cohen for her middle age, and back maybe to “Beautiful” or “Parsley, Sage…” for her old age.

What other professions have you worked in? What’s something about you that your readers wouldn’t know?

I babysat, I addressed envelopes for the Arizona Revenue System, I worked in a Phoenix dress shop, and then designed and made 50s felt skirts for them. I got a summer job as a junior reporter on the Phoenix Gazette, I was a (very bad) secretary for the 92nd St. Y in New York, and spent a summer as a receptionist at The New Yorker under Wallace Shawn. What readers might not know is that while I was married to a theatre director, I designed costumes for undergraduate productions at SUNY Binghamton, and then for the National Theatre of Belgium, and then for the Gardner Centre for the Arts at the University of Sussex in England. My three granddaughters always had made-to-order costumes, for Halloween or just for fun. The granddaughters have grown and I seem to have given up sewing, which I regret in a vague and intermittent way.

Another thing readers might want to know (and I definitely want them to know) is that all my out-of-print novels are being reissued by the indie house Michael Walmer in the U.K., starting with Descend Again and The Dancer from the Dance, which are already out and available here, and Eyes, which will come out at the same time as Simone in Pieces.

What books did you read (for research or comfort) throughout your writing process?

For this novel, Simone in Pieces, I really did less research than usual because I was drawing on my experience of the institutions (real and imagined) Simone attends or works for. Still, I needed Steve Rose’s The Making of Memory for the neurology experiments (teaching goldfish to swim mazes) of the central character Leo, and Lenore Terr’s Unchained Memories to understand the suppression and dissociation of my protagonist. I researched Paul de Mann and read Jacques Derrida’s posthumous assessment of his unmasking, “Like the Sound of the Sea Deep within a Shell.” I had to reacquaint myself with T.S. Eliot and Sylvia Plath because certain chapters and characters are based on his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and her collection of Letters Home. For comfort, I could not tell you how many or which books I read in those thirty years!

What advice would you give your past self at the start of your writing journey?

If you care about it, don’t give up. Don’t give up. Don’t give up. When a piece is going very badly, so that you lose interest entirely, put it away and trust that if it needs to be written, it’ll be there when you’re ready. If, after a few months, you find you don’t care, let it go without regret. If it still plucks at you, let yourself do a few small stitches: pick a prompt at random to get into your protagonist’s head; make a list of what’s yet to be done, or try a little from some other point of view. And above all, don’t dread; do.

What’s one thing you hope sticks with readers after they finish your book?

How people meet and part and affect each other’s lives very much or not at all, and these random encounters are the stuff of life. How we never know, really, how our lives may have touched others, what chance remark or incident may be remembered fifty years later, what infinitesimal cruelty or kindness may make all the difference to another human being.

Are you a writer, too? Submit your manuscript to Atmosphere Press.

Atmosphere Press is a selective hybrid publisher founded in 2015 on the principles of Honesty, Transparency, Professionalism, Kindness, and Making Your Book Awesome. Our books have won dozens of awards and sold tens of thousands of copies. If you’re interested in learning more, or seeking publication for your own work, please explore the links below.